During our graduate seminar, we read Vanessa Ogle’s The Global Transformation of Time 1870 to 1950, which presents the story of a critically important alteration to the global system – the evolution of standardized and measured time.

Although Ogle demonstrates that the globalization and standardization of time was a slow and uneven process, rife with nationalist competition and cultural conflict, the establishment of uniform time had substantial effects.

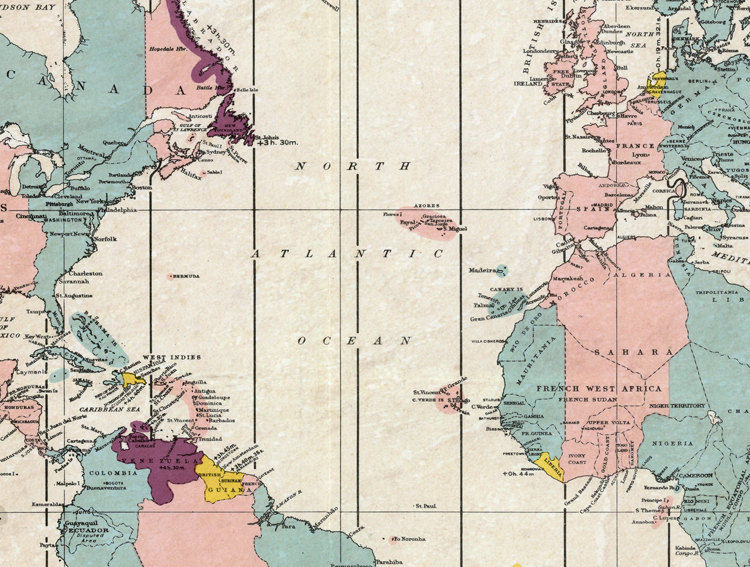

This transformation was the movement from decentralized practices of measuring time, often based on natural phenomenon like the sun or the changing seasons, to a standardized time divided up into equal length pieces that we conceive of today as seconds, minutes, days, and months. Further, this transformation was characterized by the standardization of time in one place in relation to another place, through the implementation of 24 time zones.

This ‘transformation of time’ was made possible by a nearly simultaneous transportation revolution, which greatly accelerated the speed at which people and goods could move from one place on the globe to another.

In the 1700’s – it took nearly six weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean from Europe to North America. In 1845 – thanks to the invention of steam powered ships, the journey took only 14 days. By the 1950’s, with humanity taking to the skies, the journey had been cut to 14 hours by propeller plane and a mere 8 hours by jet.

Few places can tell the story of these dual revolutions better than Detroit.

Time and Transportation On the Erie Canal

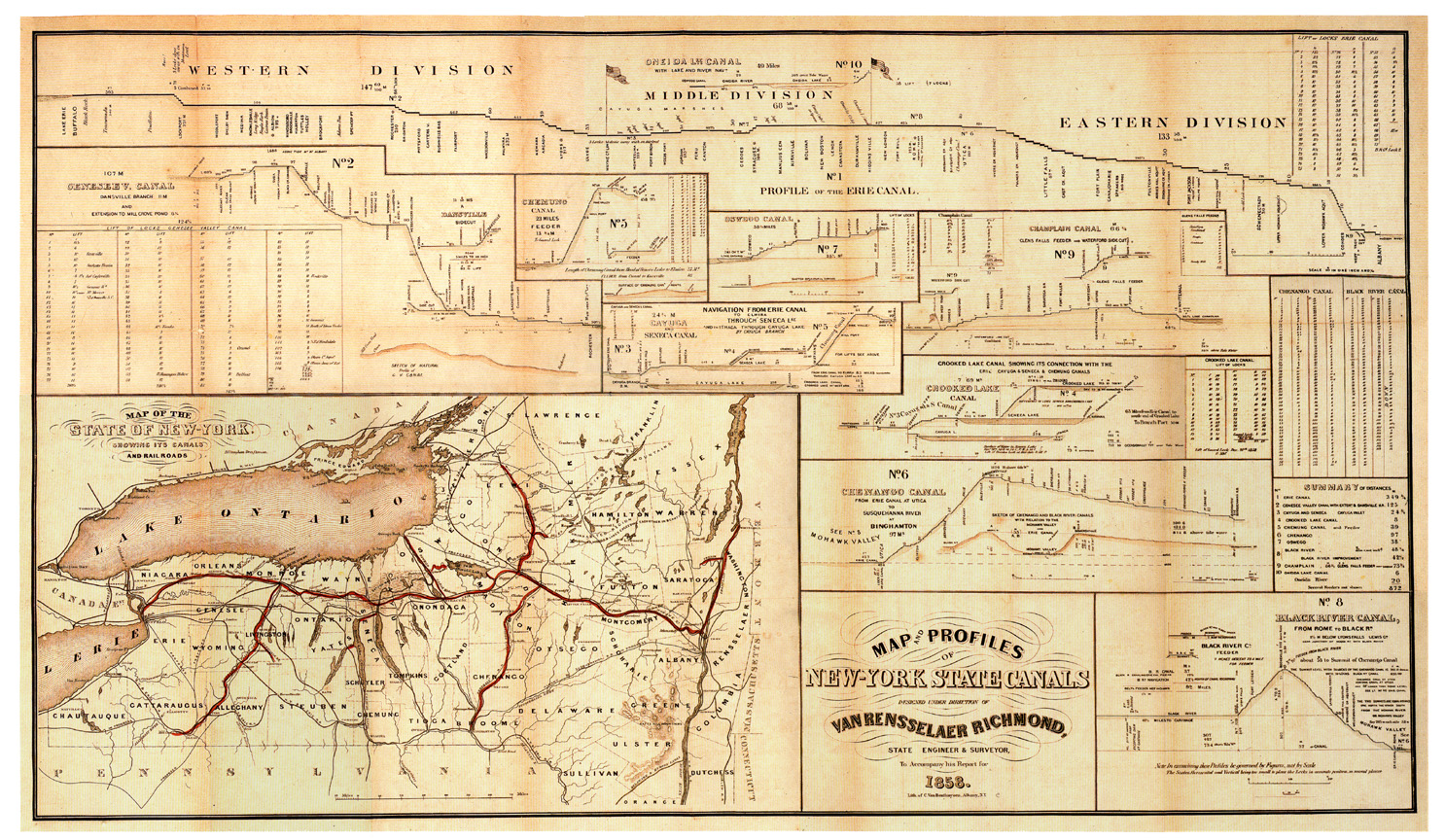

Michigan and Detroit began to feel the effects of these revolutionary transformations in 1825, with the opening of the Erie Canal, which created a navigable waterway between Buffalo on Lake Erie to the Hudson River. Before the Canal, the journey to the Atlantic took weeks of dangerous navigation on the Great Lakes, but now the trip was a relatively leisurely sail that lasted a few days.

Michigan’s natural resources and farmers were now linked to markets in the East and abroad like never before, and the cost of transportation plummeted from $100 per ton to less than $8 per ton.

George Endicott – 22 Nassau St., N.Y., ca. 1837 (BostonRareMaps)

The opening of the Erie Canal rapidly accelerated the pace at which the Michigan Territory was settled, as farmers and their families flocked from New York and New England via the Canal. Michigan’s population exploded from 9,000 people in 1820 to 32,000 people in 1830. By 1840 – 212,000 people by 1840.

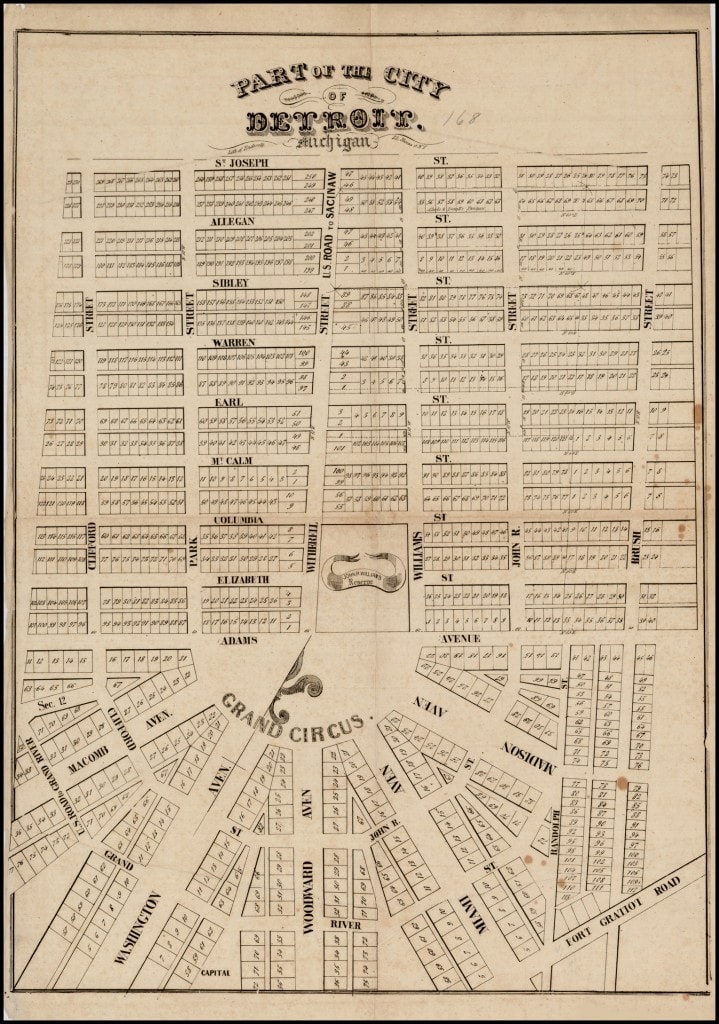

In Detroit, the population grew from approximately 5,000 residents in 1834 to nearly 10,000 residents by 1837. The Panic of 1837 slowed growth for a moment, the population of Detroit fell to about 9,000 residents in 1840, but by 1850 the growth resumed, and the population reached 21,000 residents.

In 1807, Robert Fulton perfected the Clermont Steamer, the world’s first viable steam-powered method for transportation over water. Although operators along the Erie Canal were slow to move from horse-drawn boats for a variety of technical and logistical reasons, steamboats were regularly seen operating on the canal by 1842. By 1853, there was a regularly operating “steamboat express” between Buffalo and Lockport, NY, the point where the Canal meets the Hudson River.

In 1861, steamboats that operated on the Erie Canal traveled about 6 miles per hour with the pulling power of about 16 horses. Steam-powered tugboats that could pull up to six barges at a time.

Annually, improvements were made to the Canal to accommodate the enhancements made to steam-powered vessels. By the time of the Civil War, steamboats on the Eric Canal operated with 80 horsepower.

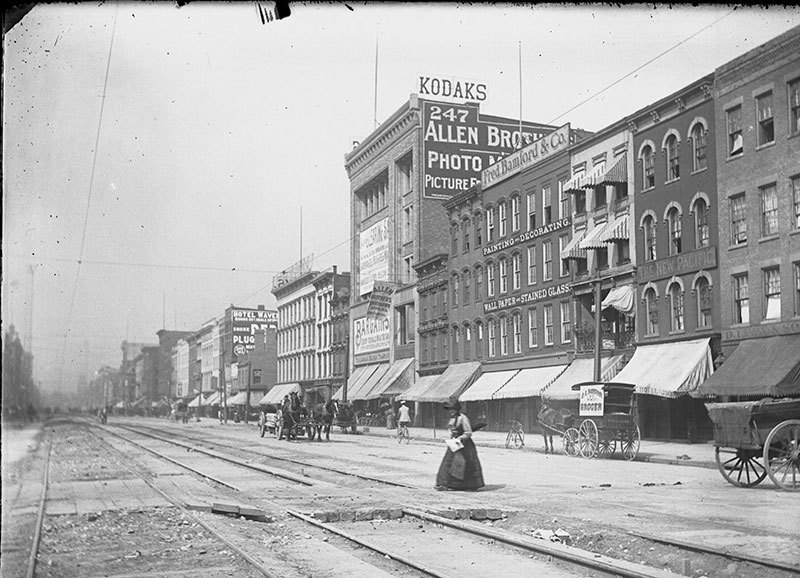

Detroit became a hub for both settlement and for exports back east, and this transformation occurred in a relatively short 25 or so year period after the opening of the Canal. By the 1850’s, Detroit was the center collection depot for agricultural products grown in Michigan and elsewhere in the West, the harbor from which products would be shipped, and a blossoming city hosting over 5,700 homes, 350 stores, 166 offices, 50 taverns, and 27 churches.

Historian George N. Fuller, writing in 1917, describes Detroit:

“[Detroit] became a rendezvous for settlers and a clearing-house of ideas about the interior (…) frequently settlers who intended to go to the interior or further west to Wisconsin and Illinois made only tentative plans until they should reach Detroit, where many were induced to settle within its limits or its vicinity (…) which in turn would put new life currents circulating through the rural districts.”

Industrial Detroit

In 1853, a shipbuilder named Eber Brock Ward organized his Eureka Iron and Steel Works in Wyandotte, Michigan – about 12 miles south of central Detroit. Ward sought to capitalize on the improved access to iron ore from the Upper Peninsula, and adapted the revolutionary new steelmaking process developed by Henry Bessemer in England. Ward was rewarded for his efforts by becoming the Detroit region’s first ever manufacturing millionaire.

The Bessemer Process was revolutionary because it swiftly increased the magnitude and speed of steel production, while also diminishing its production costs by a factor of nearly 80%. The Bessemer Process would become the standard method for the steel industry for the next century.

The American Civil War broke out in 1861, and as with elsewhere in the United States, Michigan and Detroit were deeply affected. Approximately 90,000 soldiers from Michigan (about 1 out of every 4 males) served in the war, and more than 14,000 of them never came home.

However, despite the human cost the Civil War took from Michigan, the economy expanded and became more interconnected with the outside world. Supplies of cotton previously provided by the American South were cut off, and sheep farms in Michigan helped generate its replacement – wool. Michigan’s grain outputs doubled during the war.

Most importantly for Detroit’s economy, the Civil War called for a massive increase in metalworking, and Detroit answered with its developing industrial infrastructure ready to respond. Detroit factories began to produce blades for Union lances, stoves, smelted copper, forged iron, and railroad cars.

During the second half of the twentieth century, Detroit’s dependence on the export of agricultural products and natural resources waned, and heavy industry took over. Though the lumber and mining industries mostly died out by 1900, the barons of those industries retained considerable wealth, which they began to invest in Detroit’s manufacturing sector.

Motor City, USA

The movement away from agriculture and resource extraction toward manufacturing in the latter half of the nineteenth century set the stage for the birth of Detroit’s most iconic industry – the automobile.

When considering the revolutions of time and transportation, the automobile was one of the most transformative and influential inventions of all time. Not only in the United States, but around the world, the automobile fundamentally reshaped concepts of mobility, distance, leisure, business, housing, urban planning, and regional relationships.

Attempts at similar technologies, essentially replacing the horse with an engine and put it in the hands of a human using a wheel, had been going on for some time.

Prototypes of steam cars, electric cars, and gasoline cars were competing with one another worldwide – developed by ambitious entrepreneurs from places like Prague, Vienna, Stuttgart, London, Iowa, Chicago, and Wisconsin.

Although Karl Benz, upon revealing his Benz Patent-Motorwagen in 1885, is often credited with inventing the first vehicle propelled by an internal combustion engine – it was in Detroit that the automobile was created for the world.

Individuals such as Ransom L. Olds in Lansing and William Crapo Durant (grandson of one of Michigan’s great lumber barons and former Governor Henry Crapo, and eventual founder of General Motors) achieved success in the automotive industry, but it was Henry Ford that would transform the region and the world.

Henry Ford experimented with designs for a horseless carriage while working as an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company, before setting out on his own. In 1908, Ford introduced his Model T, designed as a dependable, durable, and affordable automobile.

To develop his model, Ford focused on developing techniques of mass production, which would reduce costs and increase the speed at which automobiles could be manufactured.

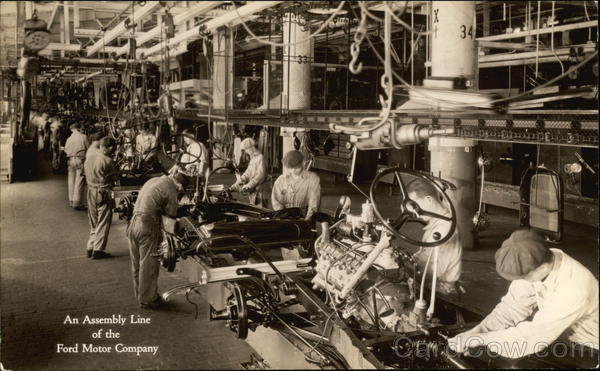

Ford’s vision of mass production gave the world a monumental manufacturing innovation – the assembly line. The assembly line did not only revolutionize the automobile industry, it accelerated the speed and amplified the scale at which mass industry itself operated.

The assembly line centered around a conveyor belt, at which each worker would be placed at a designated position and repeat the same task for their entire shift. Each position along the belt served a predetermined task progressing toward final, completed automobile.

This process was much more efficient than a small crew working on an automobile from start to finish and allowed for the replacement of skilled tradesmen with unskilled laborers that only need to be trained in a single, simple, and often tedious task, which drastically reduces labor costs.

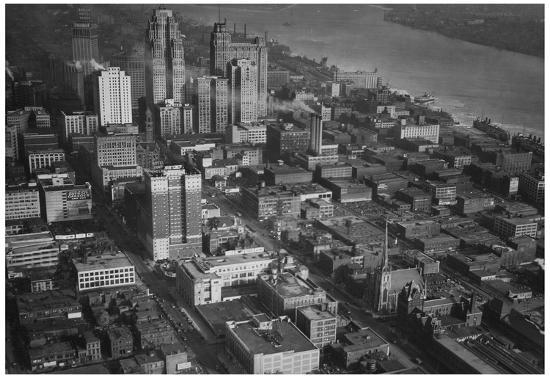

The automobile and Ford’s methods of productions were monumental technological achievements and served as lucrative payoffs for Detroit’s wealthiest investors. Detroit was no longer had a mixed identity that included frontier town, agricultural export harbor, and developing city – it was now a certifiable global center for industry and innovation.

The growing automobile industry and its ancillary industries led to yet another migratory explosion. Detroit’s population grew from 466,000 residents in 1910 to 1.6 million residents by 1930, placing it as the 4th largest city in the United States, behind only New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

This growth was clearly fueled by the automobile industry, and the economy grew increasingly concentrated on this sector. In 1910, census data reported that the automobile industry (a new category in the census in 1910) employed 5,304 workers in Detroit. In 1920, the census reported 35,000 workers in the sector, and by 1930, that number swelled to 158,000 workers. By 1940, 60% of the world’s automobiles were produced in Detroit.

Motivated by the burgeoning automobile industry and the growing realization that the automobile was quickly becoming the preferred method of travel, the Michigan state government began experimenting in roadway improvements. In 1909, the Wayne County Road Commission used a one-mile long stretch of Woodward Avenue to test out the novel idea of a concrete covered road. Mud roads and roads covered with timber were unreliable, subject to weather disruption, difficult to operate a vehicle on, and limited the ever-increasing desire for speed.

The experiment was a massive success. Engineers from around the United States and the world came to Detroit to inspect the concrete road innovation and returned home to implement it. In 1909, there was about 394,000 square yards of concrete road laid in the entire United States – most of it on Woodward Avenue in Detroit.

By 1914, just five years later, there was 19.2 million square yards of concrete road nationwide. In 1916, Congress passed the Federal Road Aid Act – promising $75 million in matching federal funds to local governments to improve roads – and in 1921, Congress passed the Federal Highway Act, an early piece of legislation that would lead to the system of highways and interstate freeways that connects the United States today.

Roads transformed the way that distances could be traveled and minimized the time to move from one place to another, and all of it could be done with the use of a relatively affordable and durable automobile. Roads made it possible for people to live in one place and work in another, leading to suburbanization and urban sprawl, radically changing the concepts urban planning and regional organization.

Along with the revolution of production brought on by the automobile and the assembly line, there was also a revolution of consumption.

As with the other themes that we have discussed, the scale and speed of consumerism would never be the same. Many of Henry Ford’s competitors envisioned the automobile as a luxury item for the wealthy, as an expensive symbol of social status.

Ford, on the other hand, realized the tremendous power that could be achieved from mass consumption, and what the correct use of the mass market could do for cutting costs, increasing profits, and altering society. As Ford’s production output roughly doubled annually (from 18,664 cars in 1910 to 533,755 cars in 1919), he also halved the retail price of his cars over the same period (from $950 in 1910 to $525 in 1919). Ford’s market continued to expand, as the growing middle class was able to afford to purchase a car, and so did his wealth.

Unfortunately, there is also a darker side to these revolutionary changes. Though the automobile, roadways, and industrial expansion served to connect humans to each other like never before – the increasingly automated nature of labor dehumanized the work experience.

Skilled tradesmen were to be replaced with unskilled labor, who would to repeat the same monotonous tasks day after day. Ford himself recognized what he called the “terror of the machine” in his memoirs, and though he did generally make efforts in his own business to practice fair wage practices, the transformative effect of the assembly line on human labor could not be reversed.

Sources Consulted can be viewed here, and are arranged by section.

Images are not cited in bibliography, if I used an image that is yours and you would like me to take it down, please contact me here.

All content on this page is the original writing of Robert Brehm, based on his research findings. If you would like to use anything above, please cite this page. Thank you!